By: John Fiore, PT

As runners, our feet take a beating. The human foot is designed with locomotion in mind. Healthy foot function hinges on a balance of mobility, strength, and support. When one of these three necessary components is compromised, injury risk increases.

Foot Anatomy

Understanding the foot and how to avoid a few common foot injuries will enable runners to run with confidence. The human foot contains 26 bones and nearly 100 joint surfaces. In addition, our feet absorb 2.5 to 5.0 times our body weight with each foot strike. The bones of the foot form three distinct structural and functional units. The rear foot is made up of the large calcaneus and talus. The rear foot is designed for weight bearing and articulates with the lower leg bones (tibia, fibula). The mid foot is made up of the navicular, talus, and cuneiform bones. The mid foot has a dual role. It absorbs shock during weight bearing and forms the stability we rely on (the arch) when pushing off to initiate the next step. The fore foot is made up of the five metatarsal bones and 14 bones in our toes (phalanges) and plays a role in terrain adaptation and balance.

Foot Mobility

Foot mobility creates shock absorption and terrain adaptation. During the walking and running stride, foot function changes from one of shock absorption to one of propulsion which means the foot must stiffen to lift our body weight against gravity for the next step or stride. Foot stiffness during all phases walking or running greatly increases the impact through the joints of the foot. Mobilizing the foot by rolling over a small ball or self -massage is a simple way to insure foot mobility.

Foot Strength

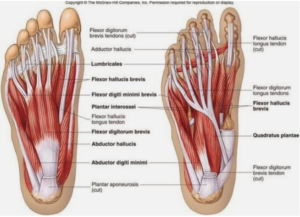

The bottom of our feet has four layers of muscles (called intrinsic foot muscles) which support the arch and provide dexterity to our toes. The lower leg muscles control the function and support of our ankle and feet collectively.

The calf muscle group (gastric-soleus), for example, is crucial for propulsion and Achilles tendon health.

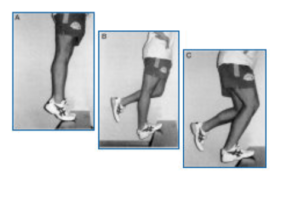

A progressive calf loading program tailored to your abilities and goals is a great place to start. A 31% reduction in calf muscle strength naturally occurs between the ages of 20 and 60 (DeVita, et al 2016), making lower leg, Achilles, and foot injuries more prevalent in runners over the age of 40. Strengthening the medial and lateral ankle (tibialis posterior, fibularis musculature) is important as well to improve ankle stability. It is important to have a physical therapist evaluate your unique foot and ankle function (strength, range of motion, joint mobility, tissue tension) in order to create a strengthening-loading program which is right for you.

Foot Support

Strong, mobile feet equal healthy feet with adequate support for running. Many of us, however, have feet which are less than ideal either due to genetics (thanks for the bunions Grandma), prior injury, or surgery history.

In some cases, therefore, the use of an insole or custom orthotic may be needed to support the foot and ankle. A custom orthotic is a medical device with the goal of placing the foot and ankle in a neutral position. Activity goals, prior injury and medical history is factored into the design of each pair of custom orthotics. Sapphire Physical Therapy makes custom orthotics on-site using the Amfit system which allows for an accurate, custom fit. Orthotic materials (based on activity, medical history, foot type) range from soft to semi-rigid carbon fiber and everything in between. Watch for our October orthotic special (20% off all orthotics) or contact John Fiore (john@sapphirept.com) or see our website to find out more about custom orthotic options or to discuss a foot-ankle strengthening program to keep you running strong.

References

DeVita P, Fellin RE, Seay JF. The relationship between age and running biomechanics. Med & Sci Sports & Exerc. 2016; 48 (1): 98-196.

McKean KA, Manson NA, Stanish WD. Musculoskeletal injury in the masters runners. Clin J Sport Med. 2006; 16 (2): 149–54.