By: Rylin Fox, PT, DPT

If you are around 35 years old or older, you are now in possession of an “aging body” that requires a little extra TLC (tender loving care) to continue operating like it did only a few years ago. As we age, there are many well-known natural and normal changes that affect many body systems, including our cardiovascular, respiratory, endocrine (think metabolism), reproductive, and immune systems, to name a few.

An often overlooked bodily system that undergoes many age-related changes is the musculoskeletal system, particularly our muscles. These changes happen gradually through our 30s and 40s and progress more quickly from 60-70 years of age (1). The goal of this article is not to make you feel depressed or fear the future, particularly if you are in the prime years of muscle development and performance that occurs between the ages of 20 and 30. Rather, the aim is to discuss the importance of continuing to stress and load your muscles as you age. Sadly, running alone isn’t enough!

Muscles and Aging

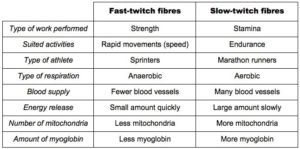

A muscle is made up of two different types of muscle fibers/cells or a combination of the two. These fibers function differently, and both have equal importance. One fiber type, the slow-twitch muscles, turn on first produce less force and are slow to fatigue – think endurance. Examples include the muscles in the back of the leg and many muscles in the back. The other type are our fast-twitch muscles which provide quick and forceful bursts of energy but fatigue faster. Examples include the big muscles in our upper arms and quadriceps on the front of the thigh.

As a body ages, the amount of fast twitch muscle fibers/cells decrease, which contributes to a decrease in muscle strength. This process can begin in the early to mid-30s, during which a person can lose an average of 3-8% lean muscle mass per decade (2). This rate decreases to 3% per year when that person reaches age 70 (3). This decline is associated with increased frailty, decreased energy, and functional decline.

Again, the point is not to depress you. Vast bodies of literature have shown that this process can be prevented or slowed with strength training. In other words, use it or lose it. Muscles need to be used regularly and placed under load to stop degeneration and atrophy. Rigorous exercise isn’t required to do so – even moderate exercise helps maintain muscle mass (4).

Recommendations for Maintaining and Building Muscle

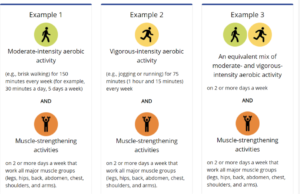

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have synthesized relevant literature to make key recommendations for exercise to include at least “two muscle-strengthening activities of moderate or greater intensity” involving both the upper and lower body per week (5). You can read more about these recommendations in The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans put out by the CDC, which updates this guidance with frequent new editions (6).

Additionally, older individuals can do more than just maintain strength. With an appropriate and comprehensive strength program, it is possible to increase muscle mass and prevent the loss of our fast twitch fibers as aging occurs.

If you identify as occupying an “aging body” and do not yet have a regular strength-building program, it is time to begin implementing one.

Benefits of Exercise for the Aging Body

The benefits of exercise are many. Not only will you be able to perform better and longer on runs and other chosen activities, but you will also enjoy a range of other associated health benefits. In fact, exercise affects our bodies in a wide variety of ways:

- Boosts cognition and reduces anxiety

- Helps with balance and coordination

- Improves bone density

- Increases cardiovascular health – heart, lungs, and general circulation in the body

- Bolsters metabolism by helping the body better process oxygen and use fat stores

- Reduces the risk of diabetes by improving the body’s ability to utilize insulin

- Manages chronic pain, including arthritis pain

- Prevents injuries and falls

Examples of Upper and Lower Body Strength Training for Runners

Bicep curl to overhead press – keeps the shoulders strong and protects the neck for carrying weight

Lat pulls – will help with poling and arm swing

Squats with front-racked weight – Helps to load the lower legs as well as core and back

Side stepping with band resistance (both directions) – keeps the hip stabilizers strong

Questions?

If you have any questions about your strength training program or need help in establishing one, physical therapists are excellent resources for helping you. We at Sapphire Physical Therapy are here to help you stay on track towards your goals for improved, pain-free movement and will take into account your specific activities whether you want to participate in intense sport, moderate recreation, or simply be able to garden and enjoy family time.

References

- Patrick N. Siparsky, Donald T. Kirkendall, William E. Garrett, Muscle Changes in Aging: Understanding Sarcopenia. JrSports Health. 2014 Jan; 6(1): 36–. 40. doi: 10.1177/1941738113502296.

- Evans WJ. Skeletal muscle loss: Cachexia, sarcopenia, and inactivity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1123S-1127S.

- Goodpaster BH, Park SW, Harris TB, et al. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:1059-1064.

- Knight J et al (2017) Anatomy and physiology of ageing 10: the musculoskeletal system. Nursing Times [online]; 113: 11, 60-63.

- https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

- https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-10/PAG_ExecutiveSummary.pdf