By: John Fiore, PT

The hamstring is an important and complex muscle group used in running. While minor hamstring pulls and strains are fairly common in runners, proximal hamstring overuse injuries can be very debilitating. Repetitive micro-trauma in the hamstring attachment site (ischial tuberosity of the pelvis) may result in proximal hamstring tendinopathy (acute tendinitis or chronic tendinosis). While proper diagnostic testing is key (clinical testing by an experienced physical therapist, real-time ultrasound by a sports physician), insufficient or incorrect treatment of proximal hamstring tendinosis can shut a runner down for months.

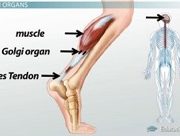

Understanding the hamstring musculature is the first step. Unlike most muscles in the human body, the hamstring crosses two joints (hip and knee) and plays a role in two distinct movements. The hamstring’s primary function is to flex or bend the knee. If your knee bends, you can thank your hamstring for its work. The hamstring’s secondary function is to aid in extending the hip. Because the hamstring crosses both the hip joint and the knee joint, it is a key muscle in the running stride. Understanding the hamstring is the first step in preventing and treating hamstring related running injuries.

Understanding the hamstring musculature is the first step. Unlike most muscles in the human body, the hamstring crosses two joints (hip and knee) and plays a role in two distinct movements. The hamstring’s primary function is to flex or bend the knee. If your knee bends, you can thank your hamstring for its work. The hamstring’s secondary function is to aid in extending the hip. Because the hamstring crosses both the hip joint and the knee joint, it is a key muscle in the running stride. Understanding the hamstring is the first step in preventing and treating hamstring related running injuries.

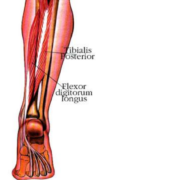

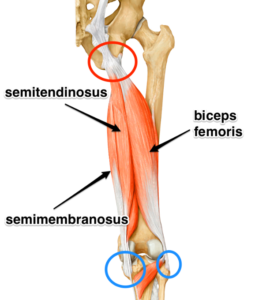

The hamstring is comprised of three muscles. All three hamstring muscles originate on the ischial tuberosity of the pelvis. The semimembranosus and semitendinosus muscles attach on the medial side of the lower leg (tibia) below the knee. The biceps femoris attaches on the lateral side of the lower leg (tibia) below the knee.The hamstring muscle group works in opposition to the quadriceps muscles. When you are flying down a hill at full speed, quads pounding and quads burning, the hamstrings act as the “brakes” to prevent knee hyperextension and to initiate the push-off phase of running.

Once diagnosed with a series of clinical tests by your PT which place tension on the hamstring origin or attachment, establishing a proper treatment progression is crucial. Strengthening the hamstring in a lengthened state (eccentric) versus a shortened state (concentric) will result in hamstrings which are strong and more prepared to check the power of the quadriceps while running. Core strength addressing lower abdominal, hip, gluteal, and lumbar strength in a functional manner will complement hamstring-specific strengthening to reduce overuse associated tissue micro-trauma.

Decreasing pain is only one component of a proximal hamstring injury prevention and treatment plan. Strengthening the hamstring in a manner consistent with running is key in preventing injury recurrence. You can go to the gym five days a week and do hamstring curls to strengthen your hamstrings but continue to have pain while running. The key to effective treatment lies in understanding the hamstring’s role while running. A video running analysis is a helpful way to detect underlying running compensations and cadence which may influence running stride which increases hamstring stress.

A qualified physical therapist skilled at applying pain-relieving modalities, integrated dry needling, deep tissue release-mobilization, muscle energy techniques to balance pelvis symmetry, active release techniques, and contract-relax techniques will address pain and tissue restriction in the hamstring secondary to overuse. An eccentric hamstring strengthening program based on your pain, compensations, and goals will build tensile strength in your hamstring and tendinous attachments. Ruling out underlying pathology (such as lumbar spine referred pain) is important as well. Finally, do not forget to roll, release your hamstrings to decrease muscle and tendon tension. A few exercise examples are illustrated below, but see a qualified physical therapist to rule out underlying injuries, referred pain, and for the gradual addition of strengthening exercises when appropriate. Call or email John, Holly, or Jesse at Sapphire PT with any questions or to schedule a consultation (406-549-5283 or john@sapphirept.com).

Proximal Hamstring and Core Exercises:

- Quadruped plank: May be modified by resting on your forearms. Do not allow your lumbar spine to extend or low back to sway-collapse.

- Side lying glut isolation: Press into the wall with your heel and maintain a neutral pelvis position.

- Quadruped hip extension: Contract the glut of your involved leg prior to extending your hip to decrease hamstring compensation.

- Glut bridging: Contract your gluts (glut max) together and hold the contraction as you raise into a bridge position and hold for 5 seconds. Slowly return to starting position and repeat for one minute. Further challenge yourself by repeating glut bridging exercise with the addition of single leg marching without allowing your pelvis to drop.

- Eccentric hamstring-strengthening exercise using the treadmill: The treadmill is turned on to a slow speed with the individual facing backward on the treadmill while holding on to the hand rails. The support side (the left leg shown) is placed off of the treadmill belt. The involved leg (the right leg shown) is extended at the hip while keeping the knee mostly extended, and the individual is instructed to resist the forward motion of the belt with the leg as the belt moves. The involved leg then is moved back to the starting point by flexing the knee and extending the hip. Continue for one minute.

- TRX hamstring curls: Lie on your back with heels hooked in TRX loops. Contract your glutes and raise your hips-pelvis off the ground. Slowly bend your knees and slowly return to a straight-knee position. Lower hips-pelvis to the floor and repeat.

Photo: www.strengthperformance.com

References:

- Cushman, D.; Rho, M., Conservative Treatment of Subacute Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy Using Eccentric Exercises Performed With a Treadmill: A Case Report. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2015, 45 (7), 557-562.

- Fredericson, M.; Moore, W.; Guillet, M.; Beaulieu, C., High hamstring tendinopathy in runners: Meeting the challenges of diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation. Physician and Sportsmedicine 2005, 33 (5), 32-43.